Central Library 600 Soledad and Southwest School of Art

| Indianapolis Public Library | |

|---|---|

| |

Central Library, the Indianapolis Public Library'southward main co-operative | |

| Established | 1873 (1873) |

| Location | Indianapolis, Indiana, United States |

| Branches | 24 |

| Access and use | |

| Circulation | 7,077,479 (2020) [1] |

| Population served | 952,389 (2019) [ii] |

| Other information | |

| Budget | $sixty,087,318 (2019) [ii] |

| Director | John Helling (Acting CEO) [3] |

| Staff | 600+[four] |

| Website | indypl.org |

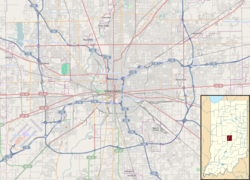

| Map | |

| |

The Indianapolis Public Library (IndyPL), formerly known as the Indianapolis–Marion County Public Library, is the public library system serving the citizens of Marion County, Indiana, United states of america and its largest city, Indianapolis. The library was founded in 1873 and has grown to include a Primal Library edifice, located adjacent to the Indiana Globe War Memorial Plaza, and 24 branch libraries spread throughout the county.

History [edit]

Memorial Presbyterian Church (ca. 1873), site of Rev. Edson's sermon ignited the motility for a public library in Indianapolis.

Postcard depicting the Indianapolis Public Library's location at Meridian and Ohio streets (ca. 1902–1903).

The Indianapolis Public Library system attributes its beginnings to a Thanksgiving Day, 1868, sermon past Hanford A. Edson, pastor of the Memorial Presbyterian Church building (which would later on get 2nd Presbyterian Church), who issued a plea for a free public library in Indianapolis. As a outcome, 113 residents formed the Indianapolis Library Association on March eighteen, 1869. In 1870, under the leadership of the superintendent of public schools, Abram C. Shortridge, citizens drafted a revision of Indiana school police force to provide public libraries controlled by a board of school commissioners. The bill passed the Indiana Full general Assembly, allowing school boards to levy taxes for the purpose of establishing and maintaining public libraries.[five]

In 1872, the public library committee of the schoolhouse lath hired Cincinnati librarian William Frederick Poole to begin a collection for the new library and appointed Charles Evans every bit the get-go librarian. Indianapolis' commencement public library opened in ane room of the Indianapolis High School edifice at the northeast corner of Pennsylvania and Michigan streets on Apr eight, 1873.[6] Upon opening, the library's collection numbered xiii,000 volumes and registered 500 borrowers. By the end of its first full yr of operation, some 3,000 patrons borrowed more than 100,000 books.[6] Afterward, equally the need for more than space grew, the library moved to the Sentinel Building on Monument Circumvolve (1876–1880) and the Alvord House at Pennsylvania and Ohio streets (1880–1893).[5]

Evans served equally librarian until 1878, and again from 1889 to 1892. Evans' successors were Albert B. Yohn (1878–1879), Arthur Due west. Tyler (1879–1883), and William deM. Hooper (1883–1889). Eliza G. Browning succeeded Evans in his second tenure, belongings the position from 1892 to 1917. During her leadership, the library moved to the first building constructed solely for its purpose, located on the southwest corner of Ohio and Meridian streets in 1893, and opened its first library co-operative opened in 1906 on Clifton Street in the Riverside neighborhood.[six] Betwixt 1910 and 1914, another 5 library branches were built with $120,000 donated by Andrew Carnegie.[6] As of 2020, two of these libraries—Eastward Washington and Spades Park—are still active branches. Prior to her resignation, Browning initiated work on a new Central Library located partially on land donated by Hoosier poet James Whitcomb Riley in 1911.[5] [6]

Charles Due east. Rush succeeded Browning, serving as librarian from 1917 until 1927. His successors were Luther L. Dickerson (1927–1944) and Marian McFadden (1944–1955). During this period, eight new co-operative libraries were opened, and the organisation's collections expanded to include films, newspapers on microfilm, and phonorecords. Additionally, bookmobile service began in 1952.[v]

Harold J. Sander, who served as director from 1956 to 1971, presided over the opening of x new branch libraries and undertook a reorganization of the Central Library in 1960 that departmentalized services. Prior to 1966, the library organisation served just those areas of the urban center under the jurisdiction of Indianapolis Public Schools, leaving more than 200,000 Marion County residents without admission to gratuitous public library services. From 1966 to 1968, the newly formed Marion Canton Public Library Board contracted with the Indianapolis Public Library for service to county residents. In 1968, the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners relinquished responsibleness for library service, assuasive the metropolis and county library systems to merge. This established the Indianapolis–Marion County Public Library as a municipal corporation serving all Marion County residents, with the exception of Beech Grove and Speedway.[5]

Raymond E. Gnat succeeded Sander as library managing director in 1972. Essential library services were computerized between 1982 and 1991. Past the early on-1990s, the public library arrangement encompassed 21 branches and three bookmobiles. In 1991, some seven million items were circulated amid 470,000 registered borrowers and 3.4 million inquiries were answered. At this time, the library collection contained nearly 1.seven million materials staffed by 410 full-fourth dimension employees.[5] Ed Szynaka served as director from 1994 until 2003, presiding over capital improvements to eight co-operative libraries, including the relocation of the Broad Ripple Branch to the Glendale Town Center.[seven] The Glendale Branch opened in 2000 every bit the kickoff full-service library at a major shopping middle in the U.S.[viii] Laura Johnston served in an acting role from 2003 to 2004 until the appointment of Linda Mielke, who served from 2004 until 2007.[vii] She was succeeded by Laura Brier.[7] Following the Great Recession and a successful state ballot measure to cap property taxes in 2008, the Indianapolis Public Library faced a budget shortfall of $4 one thousand thousand in 2010.[9] [x] Afterward considering closing half-dozen branches, officials decided to reduce co-operative hours past 26 percent, layoff 37 employees, and increase fines.[7] [11] [12] [xiii]

Jackie Nytes served every bit the primary executive officer from 2012 until 2021, when she stepped downwardly from her position.[14] [15] [16] During Nytes' leadership in 2014, the library board received approval from the Indianapolis City-County Council to consequence $58.5 1000000 in bonds to renovate and relocate existing branches and construct new ones during the following decade.[17] [eighteen] In Apr 2016, the boards of the Indianapolis and the Beech Grove public libraries voted to merge, with the Beech Grove library condign the 23rd branch library of the Indianapolis organisation on June 1, 2016.[19] John Helling was named interim principal executive officeholder at the August 23, 2021, board coming together until a search for a new CEO is completed.[20]

In 2021, the Indianapolis Public Library terminated its late fee policy, waiving fines for more than 87,000 accounts for overdue items.[21]

Services [edit]

Website and digital holdings [edit]

The library website provides admission to the library's itemize, online collections, digital archives, and subscription databases. The Bibliocommons catalog allows users to search the library'southward holdings of books, journals, and other materials and allows cardholders to asking books from any branch and have them delivered to any co-operative for pickup.

IndyPL gives cardholders complimentary admission from home to thousands of current and historical magazines, newspapers, journals and reference books in subscription databases, including EBSCOhost, which contains total text of major magazines, the Indianapolis Star (1903 - nowadays), and the New York Times (1851–present).[22]

The Indianapolis Public Library Digital Archives (Digital Indy) is a freely accessible database of over 200,000 digital images and recordings of cultural and historical interest. The collections in this archive highlight Indianapolis schools, arts organizations, neighborhoods, governmental institutions, and other groups.[23]

The library offers the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, a free-access, spider web-based encyclopedia providing comprehensive social, cultural, economic, historical, political, and physical descriptions of Indianapolis. The updated Encyclopedia of Indianapolis was created in partnership with The Polis Center of Indiana Academy–Purdue University Indianapolis and several other major historical and cultural institutions, and builds on the information featured in the original print encyclopedia published The Polis Centre in 1994.[24]

[edit]

The public library offers library services to Indianapolis schools and museums through its Shared System services. The organisation allows members and students to use their IndyPL library cards to borrow materials from their own library as well as IndyPL's collection through the library's catalog. Local museums and special libraries sharing the itemize include the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, the Indiana Medical History Museum, the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, the BJE Maurer Jewish Community Library, and Riley Children's Hospital.[25]

Central Library [edit]

| Central Library (Indianapolis–Marion County Public Library) | |

| U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

Front of Central Library from the American Legion Mall | |

| Show map of Indianapolis Show map of Indiana Bear witness map of the Usa | |

| Location | xl E. St. Clair St., Indianapolis, Indiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°46′42″North 86°9′24″West / 39.77833°N 86.15667°W / 39.77833; -86.15667 Coordinates: 39°46′42″Northward 86°9′24″West / 39.77833°N 86.15667°W / 39.77833; -86.15667 |

| Area | 1 acre (0.forty ha) |

| Built | 1917 |

| Architect | Paul Cret; Borie and Medary Zantzinger |

| NRHP referenceNo. | 75000045[26] |

| Added to NRHP | August 28, 1975 |

South pinnacle architectural render of the Central Library from 1913.

The Central Library building was designed by Philadelphia-based builder Paul Philippe Cret (with Zantzinger, Borie and Medary).[27] The original Key Library edifice was constructed in Greek Doric style architecture, faced with Indiana limestone on a Vermont marble base. Central Library opened to the public on Oct viii, 1917.[five]

Central Library contains a number of distinguished architectural design elements. The main reading room 100 feet (30 m) by 45 feet (xiv m) inside the master entrance has two flights of Maryland marble stairs, 2 30 feet (nine.one m) diameter bronze low-cal fixtures, and an ornamental ceiling designed past C. C. Zantzinger. The ceiling includes oil-on-sail medallions and printers' colophons accompanied by a series of bas-relief plaster plaques depicting early on-Indiana history. Reading rooms at the tiptop of each staircase accept forest paneling above oak bookcases and large leaded drinking glass windows.[5] Central Library was added to the National Register of Historic Places on August 28, 1975.

Key Library has undergone a number of expansions and renovations over the years. A 40,000-square-human foot (3,700 mtwo) annex to the Cardinal Library was completed in 1975 and restoration of historically-significant architecture was completed in the 1980s.[5] In 2001, Indianapolis-based architectural firm Woollen, Molzan and Partners was commissioned to renovate the historic building, aggrandize with a six-story addition, and incorporate an underground parking garage. The new curved-glass and steel facility and atrium would connect to the Cret-designed building, replacing the addendum built in the 1970s. The $104 meg project doubled the size of the library but proved controversial due to a number of design and construction flaws.[7] The renovated Central Library and its new atrium add-on opened on December nine, 2007, 2 years backside schedule and over budget.[28] [29] [thirty]

Indianapolis Special Collections Room [edit]

The Central Library houses the Indianapolis Special Collections Room, named for paper executive Nina Mason Pulliam. The drove contains a multifariousness of archival adult and children's materials, both fiction and nonfiction books by local authors, photographs, scrapbooks, typescripts, manuscripts, autographed editions, letters, newspapers, magazines, and realia. The drove features Kurt Vonnegut, May Wright Sewall, the Woollen family, James Whitcomb Riley, and Berth Tarkington.[31]

Other special collections [edit]

The 3,800-square-foot (350 mtwo) Heart for Blackness Literature & Civilization opened in 2017, provided past $1.3 meg in grant funding from the Lilly Endowment. The heart houses some ten,000 books, magazines, DVDs, and east-books with plans to qruple the collection to twoscore,000 items over the adjacent five years. The eye'southward window banners pay tribute to local Black figures, including former Indiana Fever basketball player, Tamika Catchings, poet and playwright, Mari Evans, and Congresswoman Julia Carson.[32] Stage Two of the project commenced after an Indianapolis City-County Council committee issued $five.3 meg in bonds for facility upgrades and projects in July 2020.[33]

In 2019, the Indianapolis Public Library, in partnership with Indy Pride and others, defended the Chris Gonzalez Collection, named for LGBTQ activist and Indiana Youth Group co-founder Christopher T. Gonzalez. The collection of 7,000 items relating to local and national LGBTQ+ history and culture were merged with the Central Library collection.[34] [35]

Branches [edit]

Besides the Central Library, the Indianapolis Public Library system operates 24 branch libraries and provides bookmobile services.

Eagle Branch and Martindale–Brightwood Co-operative reopened in new buildings in 2019 and 2020, respectively, while the new Michigan Route Co-operative opened in 2018 (replacing the airtight Flanner House Branch). Fountain Square Co-operative was closed in 2020.[36] As of July 2021, three new branches were under various phases of construction, design, or planning: W Perry in Perry Township;[37] Fort Benjamin Harrison in Lawrence, Indiana; and Glendale in Washington Township.

| Branch name | Established | Address[38] | Epitome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beech Grove Branch | 1951 (established) 2016 (absorbed) | 1102 Main St. Beech Grove, IN 46107 |  |

| College Avenue Branch | 1924 (established) 2000 (relocated) | 4180 North. College Ave. Indianapolis, IN 46205 |  |

| Decatur Branch | 1967 | 5301 Kentucky Ave. Indianapolis, IN 46221 | |

| Eagle Branch | 1960 (established) 2019 (relocated) | 3905 Moller Rd. Indianapolis, IN 46254 |  |

| Eastward 38th Street Branch | 1957 (established) 2003 (relocated) | 5420 E. 38th St. Indianapolis, IN 46218 |  |

| East Washington Branch | 1911 | 2822 Due east. Washington St. Indianapolis, IN 46201 |  |

| Fort Benjamin Harrison Branch | 2023 | planned | |

| Franklin Route Branch | 1969 | 5550 S. Franklin Rd. Indianapolis, IN 46239 |  |

| Garfield Park Branch | 1918 (established) 1965 (relocated) | 2502 Shelby St. Indianapolis, IN 46203 |  |

| Glendale Branch | 1930 (established) 2000 (relocated) | Glendale Town Heart 6101 Northward. Keystone Ave. Indianapolis, IN 46220 |  |

| Haughville Co-operative | 1896 (established) 2003 (relocated) | 2121 Due west. Michigan St. Indianapolis, IN 46222 |  |

| InfoZone Co-operative | 2000 | The Children's Museum of Indianapolis 3000 N. Meridian St. Indianapolis, IN 46208 | |

| Irvington Co-operative | 1903 (established) 2001 (relocated) | 5625 Eastward. Washington St. Indianapolis, IN 46219 |  |

| Lawrence Co-operative | 1967 | 7898 Hague Rd. Indianapolis, IN 46256 | |

| Martindale–Brightwood Branch | 1901 (established) June xx, 2020 (relocated) | 2434 N. Sherman Dr. Indianapolis, IN 46218 |  |

| Michigan Road Branch | December 15, 2018[39] | 6201 Michigan Rd. Indianapolis, IN 46268 |  |

| Nora Co-operative | 1971 | 8625 Guilford Ave. Indianapolis, IN 46240 |  |

| Throughway Branch | 1967 (established) 1986 (relocated) | 6525 Zionsville Rd. Indianapolis, IN 46268 |  |

| Southport Branch | 1967 | 2630 East. Finish 11 Rd. Indianapolis, IN 46227 |  |

| Spades Park Co-operative | 1912 | 1801 Nowland Ave. Indianapolis, IN 46201 |  |

| Warren Co-operative | 1974 | 9701 East. 21st St. Indianapolis, IN 46229 |  |

| Wayne Branch | 1969 | 198 South. Girls School Rd. Indianapolis, IN 46231 |  |

| Westward Indianapolis Branch | 1897 (established) 1986 (relocated) | 1216 S. Kappes St. Indianapolis, IN 46221 |  |

| West Perry Branch | July 17, 2021[37] | 6650 S. Harding St. Indianapolis, IN 46217 |

Notes [edit]

- 1. ^ This is based on the 2019 population gauge of Marion County, Indiana, subtracting the populations of the Boondocks of Speedway, Indiana. Residents of Speedway are ineligible to exist cardholders of the Indianapolis Public Library every bit the town maintains its own public library.[twoscore]

References [edit]

- ^ "2020 Annual Written report" (PDF). Indianapolis Public Library. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ a b "2019 Annual Study" (PDF). Indianapolis Public Library. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Our Leadership". Indianapolis Public Library. Retrieved Jan fifteen, 2020.

- ^ "Work at the Library". Indianapolis Public Library. Retrieved Baronial vii, 2020.

- ^ a b c d eastward f grand h i Bodenhamer, David J.; Barrows, Robert G. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 789–791. ISBN0-253-31222-ane.

- ^ a b c d e Butsch Freeland, Sharon (March 22, 2016). "Hello Mailbag: Indianapolis Public Library". HistoricIndianapolis.com. Retrieved August nine, 2020.

- ^ a b c d eastward McLaughlin, Kathleen (May five, 2011). "Next library CEO faces great expectations". Indianapolis Business Journal. Retrieved August nine, 2020.

- ^ Shuey, Mickey (August 17, 2020). "Library planning to buy quondam schoolhouse for new $10.2M Glendale co-operative". Indianapolis Business Journal. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Russell, John (Baronial 14, 2020). "Methodist Hospital expansion exposes tax tensions". Indianapolis Concern Journal. Retrieved Baronial 16, 2020.

- ^ Jarosz, Francesca (October 7, 2010). "Ailing library eyes new funding source". Indianapolis Business organisation Journal. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ McLaughlin, Kathleen (Apr 8, 2010). "Marion County library may close vi branches". Indianapolis Business Journal. Retrieved Baronial 9, 2020.

- ^ "Library slashes hours, to close master branch on Thursdays". Indianapolis Business Journal. September 14, 2010. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ McLaughlin, Kathleen (November four, 2010). "Library cuts 37 employees in effort to reduce deficit". Indianapolis Business Journal. Retrieved August ten, 2020.

- ^ "Urban center-County Councilor Nytes named library CEO". Indianapolis Business Journal. Oct 17, 2014. Retrieved Baronial 9, 2020.

- ^ "Our Leadership". Indianapolis Public Library. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ^ Library, Indianapolis Public (Jan 15, 2022). "CEO Jackie Nytes and Indy Library Lath…". Indianapolis Public Library . Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ McLaughlin, Kathleen (Oct 17, 2014). "Library plans $59M in new branches, upgrades". Indianapolis Business Periodical. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Warburton, Bob (December 14, 2014). "Indianapolis Approves $58 Meg in Bonds for Libraries". Library Periodical. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ "Indy Library Board approves merger of Beech Grove Library". WISHTV.com. April 28, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ August 23, 2021 Regular Board Coming together Documents-NEW Indianapolis Public Library, retrieved January xv, 2022

- ^ "Indianapolis Public Library will no longer accuse late fees, waives previous fines". The Indianapolis Star. January 12, 2021. Retrieved Apr 22, 2021.

- ^ "Research". Indianapolis Public Library. January 15, 2022. Retrieved January xv, 2022.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Explore the Indianapolis Public Library'due south Digital Archive". Indianapolis Public Library . Retrieved January 15, 2022.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ "The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis". Indianapolis Public Library. January 14, 2022. Retrieved January fifteen, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Shared System". Indianapolis Public Library. Jan 14, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ "National Annals Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Indiana Land Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD)" (Searchable database). Section of Natural Resource, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved Baronial 1, 2016. Note: This includes Lawrence Downey (July 1975). "National Annals of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Grade: Central Library (Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library)" (PDF) . Retrieved August ane, 2016. and accompanying photographs.

- ^ Megan Fernandez (June 2010). "The Pillar: Evans Woollen". Indianapolis Monthly. Indianapolis, Indiana: 73. Retrieved December 18, 2017. Come across besides: "Biographical" Sketch in Woollen, Molzan and Partners, Inc. Architectural Records, ca. 1912–2011. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. 2017.

- ^ Woollen, Molzan and Partners website project page [1] Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Swiatek, Jeff (December 21, 2007). "Storybook ending?: Next chapter in Central Library saga could yield a commercial boom for surrounding expanse". The Indianapolis Star . Retrieved January five, 2016.

- ^ Central to Our History: Indianapolis Special Collections Room, northward.d., brochure, Indianapolis, IN: Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library.

- ^ Bahr, Sarah (October 23, 2017). "Indianapolis Public Library Debuts New Center For Blackness Literature And Civilisation". Indianapolis Monthly. Indianapolis: Emmis Communications. Retrieved Baronial 7, 2020.

- ^ Quinn, Samm (July 22, 2020). "City-County Council committee approves $5.3M bail for library upgrades". Indianapolis Business Journal. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ "Indianapolis Fundamental Library unveils LGBTQ+ showroom". WRTV. Indianapolis. November 15, 2019. Retrieved Baronial 7, 2020.

- ^ Library, Indianapolis Public (Jan fourteen, 2022). "Special Collections". Indianapolis Public Library . Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ Orr, Susan (February 11, 2020). "Bargain betwixt Indy Reads, library would relocate bookstore to Fountain Square". Indianapolis Business Periodical. Retrieved August ten, 2020.

- ^ a b Mack, Justin (July 16, 2021). "Go inside Indianapolis Public Library'southward new West Perry branch, opening July 17". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "Locations & Hours". Indianapolis Public Library. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ Wilkinson, Kelly (December 13, 2018). "New library on Michigan Rd. meets neighborhood needs". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved Baronial 21, 2021.

- ^ "Get a Library Menu". Indianapolis Public Library. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

Further reading [edit]

- Drupe, Southward.L. Stacks: A History of the Indianapolis-Marion Canton Public Library. Indianapolis: Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library Foundation, 2011.

- Downey, Lawrence J. A Live Thing in the Whole Town: The History of the Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library, 1873-1990. Indianapolis: Indianapolis-Marion Canton Public Library Foundation, 1991.

- Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library. Historic Highlights. Indianapolis: The Library, 1993.

- Jean Preer (2013). "Counter Culture: The World every bit Viewed from Inside the Indianapolis Public Library, 1944–1956". In Christine Pawley; Louise Due south. Robbins (eds.). Libraries and the Reading Public in Twentieth-Century America. Print Civilisation History in Modern America. University of Wisconsin Printing. ISBN978-0299293239.

External links [edit]

- Indianapolis Public Library website

- HI Mailbag: History of the Indianapolis Public Library

janeshoudishon1948.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indianapolis_Public_Library

0 Response to "Central Library 600 Soledad and Southwest School of Art"

Post a Comment